================================

THE REVOLT AGAINST ROME

The Jewish heart had been kindled to a successful revolt under Judas Maccabæus. The memory of this triumph and of the cruelties that had forced it upon the unwarlike people, ripened the national heart for an effort against even the mighty empire of Rome. The struggle was one of the bravest and one of the most horrible in the world’s annals. It found a splendid chronicler in Josephus, who was one of the generals, and fought bravely, and yet, like his Grecian prototype, Thucydides, won his immortality by his pen instead of by his sword. Josephus’ account is, however, a voluminous work in itself, and we must be content with some of the most brilliant pages

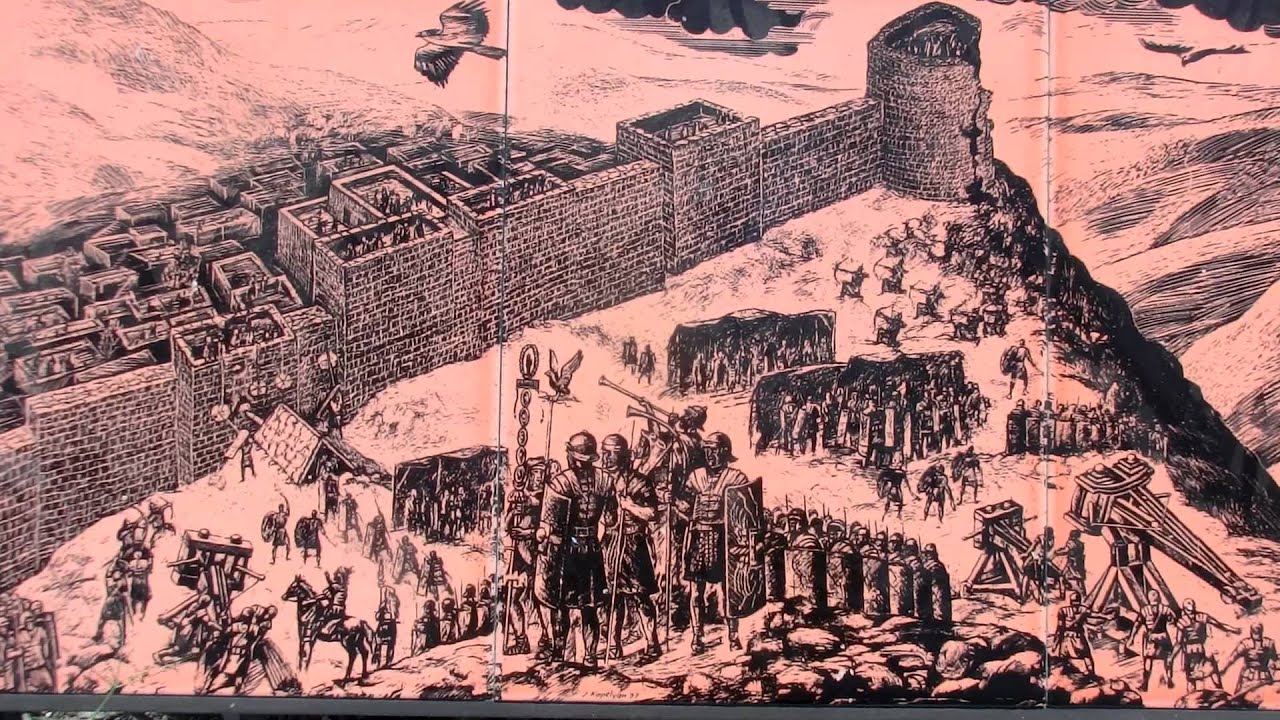

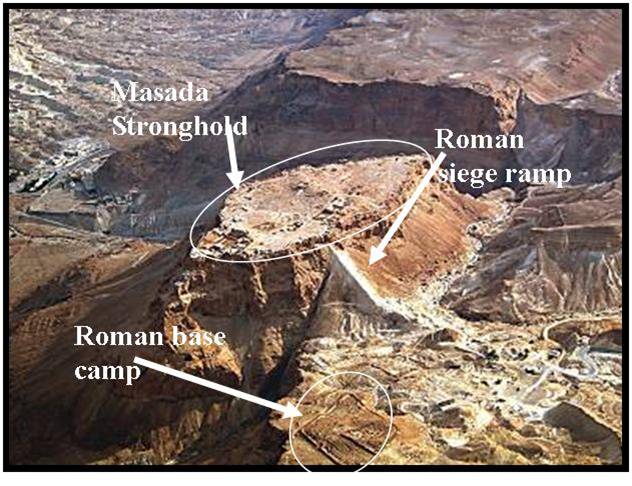

In Judea, the temper of the nation had long given warning of approaching revolt. It broke out at length when Gessius Florus was appointed procurator through the influence of his wife, who was a friend of Poppæa’s. His vexatious measures and rapacity wore out the patience of the Jews; on this point Tacitus is at one with Josephus. Disorders first occurred at Cæsarea on the occasion of Nero’s decree; then the action of Florus in taking seventeen talents out of the temple treasury provoked a riot at Jerusalem. The soldiery spread through the streets, plundering the houses and massacring the peaceable inhabitants, not sparing even women and children; after which the procurator withdrew to Cæsarea, leaving only one cohort in the tower of Antonia. The Zealots promptly occupied the temple precincts. When a government flees before the mob it may safely be predicted that the most excited and violent party will impose its will on the rest. In vain did Agrippa II and his sister Berenice, who happened to be at Jerusalem at the time, endeavour to allay the popular frenzy. They could gain nothing, in spite of the respect felt for the last descendants of the ancient kings. A band of men left the city, seized the fortress of Masada, and massacred the garrison.

The moderate party, composed of the wealthier classes and the priests, would have recoiled from an insensate struggle against the power of Rome, but Eleazar, the leader of the party of action, made the rupture final by refusing to offer in the temple the victims which were wont to be sacrificed there by the emperor’s command for the prosperity of Rome and of the empire. The friends of order sent to entreat Agrippa and Florus to come with all speed to protect them against the rebels. Agrippa sent three thousand horsemen, who took possession of the upper city, while the Zealots, robbers, and sicarii occupied the temple and the lower city. Florus returned no answer. According to Josephus, he wished the insurrection to grow to a[178] head, and, when it was exhausted by its own violence, to extinguish it in blood. Such are the habitual tactics of military leaders in time of revolution. Such deliverers deserve, as Lamennais says, to be execrated in the present and in the future.

The insurgents, who were masters of the temple, refused entrance to the partisans of peace, made their way into the upper city, and set fire to the palace of Agrippa and Berenice. They also burnt the archives, in order to destroy all vouchers of credit and so bring over the debtors to their side. They were commanded by Manahem, the son of Judas the Gaulonite, and by Eleazar, the son of the high priest Ananias, who was one of the principal leaders of the opposite party, for civil war had set division even between members of the same family. The tower of Antonia was taken and burnt by the revolutionaries, who allowed Agrippa’s horsemen to depart unmolested. The Romans, for their part, took refuge in the three towers of the old wall. Ananias, who, with his brother Hezekiah, was found hidden in an aqueduct, was slaughtered by Manahem. Then Eleazar, enraged at the assassination of his father and uncle, stirred up the people against Manahem, who now gave himself the airs of a tyrant. “It was not worth while,” he said to them, “to cast off the yoke of Rome in order to stoop to that of the least among yourselves.” Manahem was stoned in the court of the temple. Such of his partisans as could make their escape took refuge in the fortress of Masada. The Romans asked for terms of capitulation. They were promised their lives, but they had no sooner given up their arms than Eleazar and the Zealots fell upon them and slew them all but one, who consented to be circumcised. The rest died, to a man, without asking for mercy, only crying out upon the sanctity of their oaths. These imprecations filled the people with dire forebodings, all the more so because this perjury had been committed on the Sabbath day

The same day and hour, as if by the working of divine vengeance, says Josephus, a massacre of the Jews took place at Cæsarea; of twenty thousand men not one was left, for those who escaped were captured by Florus and sent to the galleys. This massacre roused the whole nation to such a pitch of fury that they ravaged the towns and villages of the Syrian frontier, Philadelphia, Heshbon, Gerasa, Pella, and Scythopolis, with fire and sword. They then sacked Gadara, Hippos, and Gaulonitis, burned Sebaste and Askalon, and demolished Anthedon and Gaza. They slew all that were not Jews. Then, as was to be expected, terrible reprisals followed. An epidemic of carnage raged all over southern Syria and extended to Egypt. Every mixed city became a battle-ground. If we are to trust Josephus, the Jews were never the aggressors. That is hard to believe. It is possible that the rabble, seeing Judea rebel against Rome, concluded that they might massacre the Jews with impunity. But it is also very probable that the insurrection had roused to the highest pitch the fanaticism of Jews settled elsewhere than in Judea, and that they were desirous of imitating the exploits of their brethren at Jerusalem. In Alexandria, as a sequel to a discussion in the theatre, the Jews armed themselves with torches and threatened to burn all the Greeks alive. The governor of the city was Tiberius Alexander, the Jewish convert to Hellenism who had formerly been procurator of Judea. He tried to make his compatriots listen to reason, but without success. He was obliged to send for the Roman legions. The Jewish quarter, known as the Delta, was heaped with corpses; Josephus speaks of fifty thousand slain. At Damascus the Syrians cooped the Jews up in the gymnasium and slew ten thousand of them. They had carefully concealed[179] their design from their wives, nearly all of whom professed the Jewish religion.

After they had succeeded in retaking Jerusalem, the Zealots occupied the fortresses of the Dead Sea district. They massacred the Roman garrison of the castle of Cypros, which commanded Jericho; that of Macherus capitulated. At length Cestius Gallus, governor of Syria, determined to take up arms against the insurrection. He started from Antioch with his legions and some auxiliary troops furnished by Agrippa, who accompanied him on this expedition, and by the kings of Commagene and Ituræa. Galilee and the seaboard were subdued, and Cestius advanced to Gabao, two leagues from Jerusalem. The city was full of pilgrims who had come up to the Feast of Tabernacles. Although it was the Sabbath day, an immense multitude marched forth, and the irresistible onset of this troop of anarchists triumphed over Roman discipline. Simon, the son of Giora, one of the bravest leaders of the Zealots, pursued the fugitives and dispersed the Roman rear-guard. Agrippa endeavoured to induce the insurgents to submit by promising them an amnesty in the name of Cestius; one party among the people was desirous of accepting terms, but the anarchists killed the ambassadors. Cestius again advanced upon Jerusalem and took possession of the outskirts of the city. The insurgents had abandoned the new city and fallen back upon the temple. If he had attacked immediately, the war would have come to an end. A member of the family of Ananus, who was at the head of the party of order, offered to open the gates to the Romans; the Zealots flung him from the walls. For five days Cestius endeavoured to storm the temple precincts. The soldiers were at work sapping the walls, sheltering themselves under their shields, in the formation known as the “tortoise” (testudo). The anarchists, losing heart, began to take to flight, and the moderate party were about to open the gates, when Cestius, deceived by false reports, or perhaps seduced by bribery, sounded the retreat, withdrew to Gabao, and—pursued and harassed by the Jews, who killed six thousand of his men—escaped under cover of night, leaving his baggage and engines of war behind.

The partisans of peace, seeing that in spite of their efforts they were embarked upon the conflict, resolved to set themselves at the head of the movement, so as to keep it within bounds if that were still possible. “Ananus,” says Renan, “took more and more the position of head of the moderate party. He still had hopes of bringing the mass of the people over to peaceful counsels; he endeavoured secretly to check the manufacture of arms, and to paralyse resistance while seeming to organise it. This is the most dangerous of all games to play in time of revolution; Ananus was, no doubt, what revolutionaries call a traitor. In the eyes of the enthusiasts he was guilty of the crime of seeing clearly; in those of history he cannot be absolved from the guilt of having accepted the falsest of false positions, that which consists of making war without conviction, merely under pressure from ignorant fanatics.” Among the peace party were some who held aloof lest they should be involved in a destruction which they regarded as inevitable. Such, for example, were some of the Pharisees, and certain doctors, careless of politics and absorbed in the study of the law, the adherents of the Herod family, and the members of the Christian church, who, since the death of James, had begun more and more to regard their cause as distinct from that of the Jews.

the rabbis who emigrated to Jabneh before the final struggle, deals somewhat harshly with the Herodians and[180] Christians. “Only such,” he says, “as rated their personal interests above those of their country, or sought the melancholy satisfaction of seeing in its ruin the triumph of their political or religious opinions, fled in the hour of peril. The friends of Agrippa openly betrayed their country by going over to the Roman side and paying court to Cestius and the emperor Nero. Among the fugitives were also the Christian Jews, following the advice given by Jesus Christ to his disciples (Matthew xxiv. 16). Preoccupied with the kingdom of Heaven, which they then seriously looked for, the Christians did not feel it their duty to meddle with earthly matters nor to take part in the defence of their unhappy country; led by Simeon, their bishop, they withdrew beyond Jordan, far from the clash of arms, and sought a refuge in the city of Pella.”

Cestius died, of disease or grief, shortly after his defeat. Nero handed over the command to Vespasian, an experienced general, who had given proof of his military capacity in Germania and Brittany. Vespasian proceeded to Syria by way of Asia Minor, while his son Titus went to Alexandria to fetch two legions and lead them into Palestine. Agrippa and some other petty kings from the country round about, Antiochus of Commagene, Sohemus, and Malchus the Arab, brought auxiliary troops to Vespasian, and at the end of the winter of the year 67, an army of sixty thousand men marched into Galilee. The government of that province had been committed by his fellow-countrymen to Josephus, the historian to whom we owe the account of the whole war; and though he was one of the peace party, he had neglected no measures for putting the country in a state of defence. The defence, which he relates in detail, was heroic. The little city of Jotapata held out with amazing resolution against arms and engines of war. Forty thousand men succumbed during the siege.c

Both as a vivid narrative and as a type of the ferocity of assault, resistance and revenge marking the battles of that time, the account by Josephus of his own ingenious and desperate defence of Jotapata is well worth citing at length. He speaks of himself, like Cæsar, in the third person

Vespasian, therefore, in order to try how he might overcome the natural strength of the place, as well as the bold defence of the Jews, made a resolution to prosecute the siege with vigour. To that end he called the commanders that were under him to a council of war, and consulted with them which way the assault might be managed to the best advantage; and when the resolution was there taken to raise a bank against that part of the wall which was practicable, he sent his whole army abroad to get the materials together. So when they had cut down all the trees on the mountains that adjoined to[181] the city, and had gotten together a vast heap of stones, besides the wood they had cut down, some of them brought hurdles, in order to avoid the effects of the darts that were shot from above them. These hurdles they spread over their banks, under cover whereof they formed their bank, and so were little or nothing hurt by the darts that were thrown upon them from the wall, while others pulled the neighbouring hillocks to pieces, and perpetually brought earth to them; so that while they were busy three sorts of ways, nobody was idle. However, the Jews cast great stones from the walls upon the hurdles which protected the men, with all sorts of darts also; and the noise of what could not reach them was yet so terrible, that it was some impediment to the workmen.

Vespasian then set the engines for throwing stones and darts round about the city; the number of the engines was in all a hundred and sixty; and bade them fall to work and dislodge those that were upon the wall. At the same time such engines as were intended for that purpose, threw at once lances upon them with great noise, and stones of the weight of a talent were thrown by the engines that were prepared for that purpose, together with fire, and a vast multitude of arrows, which made the wall so dangerous, that the Jews durst not only not to come upon it, but durst not come to those parts within the walls which were reached by the engines; for the multitude of the Arabian archers, as well also as all those that threw darts and slung stones, fell to work at the same time with the engines. Yet did not the others lie still when they could not throw at the Romans from a higher place; for they then made sallies out of the city like private robbers, by parties, and pulled away the hurdles that covered the workmen, and killed them when they were thus naked; and when those workmen gave way, these cast away the earth that composed the bank, and burnt the wooden parts of it, together with the hurdles, till at length Vespasian perceived that the intervals there were between the works were of disadvantage to him; for those spaces of ground afforded the Jews a place for assaulting the Romans. So he united the hurdles, and at the same time joined one part of the army to the other, which prevented the private excursions of the Jews.

And when the bank was now raised, and brought nearer than ever to the battlements that belonged to the walls, Josephus thought it would be entirely wrong in him if he could make no contrivances in opposition to theirs, and that might be for the city’s preservation; so he got together his workmen, and ordered them to build the wall higher; and when they said that this was impossible to be done while so many darts were thrown at them, he invented this sort of cover for them:

He bade them fix piles, and expand before them raw hides of oxen newly killed, that these hides, by yielding and hollowing themselves when the stones were thrown at them, might receive them, for that the other darts would slide off them, and the fire that was thrown would be quenched by the moisture that was in them; and these he set before the workmen; and under them these workmen went on with their works in safety, and raised the wall higher, and that both by day and by night, till it was twenty cubits high. He also built a good number of towers upon the wall, and fitted it to strong battlements. This greatly discouraged the Romans, who in their own opinions were already gotten within the walls, while they were now at once astonished at Josephus’ contrivance and at the fortitude of the citizens that were in the city.

And now Vespasian was plainly irritated at the great subtilty of this stratagem, and at the boldness of the citizens of Jotapata; for taking heart[182] again upon the building of this wall, they made fresh sallies upon the Romans, and had everyday conflicts with them by parties, together with all such contrivances as robbers make use of, and with the plundering of all that came to hand, as also with the setting fire to all the other works; and this till Vespasian made his army leave off fighting them, and resolved to lie round the city, and to starve them into a surrender, as supposing that either they would be forced to petition him for mercy by want of provisions, or if they should have the courage to hold out till the last, they should perish by famine: and he concluded he should conquer them the more easily in fighting, if he gave them an interval, and then fell upon them when they were weakened by famine; but still he gave orders that they should guard against their coming out of the city.

Now the besieged had plenty of corn within the city, and indeed of all other necessaries, but they wanted water, because there was no fountain in the city, the people being there usually satisfied with rain-water; yet it is a rare thing in that country to have rain in summer, and at this season, during the siege, they were in great distress for some contrivance to satisfy their thirst; and they were very sad at this time particularly, as if they were already in want of water entirely, for Josephus, seeing that the city abounded with other necessaries, and that the men were of good courage, and being desirous to protect the siege to the Romans longer than they expected, ordered their drink to be given them by measure; but this scanty distribution of water by measure was deemed by them as a thing more hard upon them than the want of it; and their not being able to drink as much as they would, made them more desirous of drinking than they otherwise had been; nay, they were so much disheartened hereby as if they were come to the last degree of thirst. Nor were the Romans unacquainted with the state they were in, for when they stood over against them, beyond the wall, they could see them running together, and taking their water by measure, which made them throw their javelins thither, the place being within their reach, and kill a great many of them.

Vespasian hoped that their receptacles of water would in no long time be emptied, and that they would be forced to deliver up the city to him; but Josephus being minded to break such his hope, gave command that they should wet a great many of their clothes, and hang them out about the battlements, till the entire wall was of a sudden all wet with the running down of the water. At this sight the Romans were discouraged, and under consternation, when they saw them able to throw away in sport so much water, when they supposed them not to have enough to drink themselves. This made the Roman general despair of taking the city by their want of necessaries, and to betake himself again to arms, and to try to force them to surrender, which was what the Jews greatly desired; for as they despaired of either themselves or their city being able to escape, they preferred a death in battle before one by hunger and thirst.

the city could not hold out long, and that his own life would be in doubt if he continued in it; so he consulted how he and the most potent men of the city might fly out of it. When the multitude understood this, they came all round about him, and begged of him not to overlook them while they entirely depended on him, and him alone; for that there was still hope of the city’s deliverance if he would stay with them, because everybody would undertake any pains with great cheerfulness on his account, and in that case there would be some comfort for them also, though they should be taken: that it became him neither to fly from his enemies, nor to desert his friends, nor to leap out of that city, as out of a ship that was sinking in a storm, into which he came, when it was quiet and in a calm; for that by going away he would be the cause of drowning the city, because nobody would then venture to oppose the enemy when he was once gone, upon whom they wholly confided.

Accordingly, both the children and the old men, and the women with their infants, came mourning to him, and fell down before him, and all of them caught hold of his feet, and held him fast, and besought him, with great lamentations, that he would take his share with them in their fortune; and I think they did this, not that they envied his deliverance, but that they hoped for their own; for they could not think they should suffer any great misfortune, provided Josephus would but stay with them.

Vespasian, when he saw the Romans distressed by these sallies (although they were ashamed to be made to run away by the Jews; and when at any time they made the Jews run away, their heavy armour would not let them pursue them far; while the Jews, when they had performed any action, and before they could be hurt themselves, still retired into the city), ordered his armed men to avoid their onset, and not to fight it out with men under desperation, while nothing is more courageous than despair; but that their violence would be quenched when they saw they failed of their purposes, as fire is quenched when it wants fuel; and that it was most proper for the Romans to gain their victories as cheap as they could, since they are not forced to fight, but only to enlarge their own dominions. So he repelled the Jews in great measure by the Arabian archers, and the Syrian slingers, and by those that threw stones at them, nor was there any intermission of the great number of their offensive engines. Now, the Jews suffered greatly by these engines, without being able to escape from them; and when these engines threw their stones or javelins a great way, and the Jews were within their reach, they pressed hard upon the Romans, and fought desperately, without sparing either soul or body, one part succouring another by turns, when it was tired down.

And here a certain Jew appeared worthy of our relation and commendation; he was the son of Sameas, and was called Eleazar, and was born at Saab, in Galilee. This man took up a stone of vast bigness, and threw it down from the wall upon the ram, and this with so great a force that it broke off the head of the engine. He also leaped down and took up the head of[185] the ram from the midst of them, and without any concern, carried it to the top of the wall, and this, while he stood as a fit mark to be pelted by all his enemies. Accordingly, he received the strokes upon his naked body, and was wounded with five darts; nor did he mind any of them while he went up to the top of the wall, where he stood in sight of them all, as an instance of the greatest boldness: after which he threw himself on a heap with his wounds upon him, and fell down, together with the head of the ram. Next to him, two brothers showed their courage; their names were Netir and Philip, both of them of the village of Ruma, and both of them Galileans also; these men leaped upon the soldiers of the tenth legion, and fell upon the Romans with such a noise and force as to disorder their ranks, and put to flight all upon whomsoever they made their assaults.

The noise of the instruments themselves was very terrible, the sound of the darts and stones that were thrown by them, was so also; of the same sort was the noise the dead bodies made, when they were dashed against the wall; and indeed dreadful was the clamour which these things raised in the women within the city, which was echoed back at the same time by the cries of such as were slain; while the whole space of ground whereon they fought ran with blood, and the wall might have been ascended over by the bodies of the dead carcasses; the mountains also contributed to increase the noise by their echoes; nor was there on that night any thing of terror wanting that could either affect the hearing or the sight: yet did a great part of those[186] that fought so hard for Jotapata fall manfully, as were a great part of them wounded. However, the morning watch was come ere the wall yielded to the machines employed against it, though it had been battered without intermission. However, those within covered their bodies with their armour, and raised works over against that part which was thrown down, before those machines were laid by which the Romans were to ascend into the city.

In the morning Vespasian got his army together, in order to take the city by storm. But Josephus, understanding the meaning of Vespasian’s contrivance, set the old men, together with those that were tired out, at the sound parts of the wall, as expecting no harm from those quarters, but set the strongest of his men at the place where the wall was broken down, and before them all, six men by themselves, among whom he took his share of the first and greatest danger. He also gave orders, that when the legions made a shout they should stop their ears, that they might not be affrighted at it, and that, to avoid the multitude of the enemies’ darts, they should bend down on their knees, and cover themselves with their shields, and that they should retreat a little backward for a while, till the archers should have emptied their quivers; but that, when the Romans should lay their instruments for ascending the walls, they should leap out on the sudden, and with their own instruments should meet the enemy, and that every one should strive to do his best, in order not to defend his own city, as if it were possible to be preserved, but in order to revenge it, when it was already destroyed; and that they should set before their eyes how their old men were to be slain, and their children and their wives to be killed immediately by the enemy; and that they would beforehand spend all their fury, on account of the calamities just coming upon them,

And now the trumpeters of the several Roman legions sounded together, and the army made a terrible shout; and the darts, as by order, flew so fast that they intercepted the light. However, Josephus’ men remembered the charges he had given them, they stopped their ears at the sounds and covered their bodies against the darts; and as to the engines that were set ready to go to work, the Jews ran out upon them, before those that should have used them were gotten upon them. And now, on the ascending of the soldiers, there was a great conflict, and many actions of the hands and of the soul were exhibited, while the Jews did earnestly endeavour, in the extreme danger they were in, not to show less courage than those who, without being[187] in danger, fought so stoutly against them; nor did they leave off struggling with the Romans till they either fell down dead themselves, or killed their antagonists. But the Jews grew weary with defending themselves continually, and had not enow to come in their places to succour them—while, on the side of the Romans, fresh men still succeeded those that were tired; and still new men soon got upon the machines for ascent, in the room of those that were thrust down; those encouraging one another, and joining side to side with their shields, which were a protection to them, they became a body of men not to be broken; and as this band thrust away the Jews, as though they were themselves but one body, they began already to get upon the wall.

But as the people of Jotapata still held out manfully, and bore up under their miseries beyond all that could be hoped for, on the forty-seventh day (of the siege) the banks cast up by the Romans were become higher than the wall; on which day a certain deserter went to Vespasian, and told him, how few were left in the city, and how weak they were, and that they had been so worn out with perpetual watching, and also perpetual fighting, that they could not now oppose any force that came against them, and that they might be taken by stratagem, if any one would attack them; for that about the last watch of the night, when they thought they might have some rest from the hardships they were under, and when a morning sleep used to come upon them, as they were thoroughly weary, he said the watch used to fall asleep; accordingly his advice was, that they should make their attack at that hour.

Titus himself that first got upon it, with one of his tribunes, Domitius Sabinus, and had a few of the fifteenth legion along with him. So they cut the throats of the watch, and entered the city very quietly. After these came Cerealis the tribune, and Placidus, and led on those that were under them. Now when the citadel was taken, and the enemy were in the very midst of the city, and when it was already day, yet was not the taking of the city known by those that held it; for a great many of them were fast asleep, and a great mist, which then by chance fell upon the city, hindered those that got up from distinctly seeing the case they were in, till the whole Roman army was gotten in, and they were raised up only to find the miseries they were under; and as they were slaying, they perceived the city was taken.

No comments:

Post a Comment